January 8, 2006

By Stephanie Zacharek

Nicholas Ray's "Rebel Without a Cause" (1955) is often considered a movie of symbols, all of them keyed to our feelings, and memories of youth as well as to our never-resolved disappointments: James Dean stands for youthful rebellion; Natalie Wood for the seemingly disparate appetites for wildness and tenderness; and Sal Mineo for the unpredictability, and the danger, of sexual desire. Sometimes it's easier, to grapple with what characters mean than with what they do.

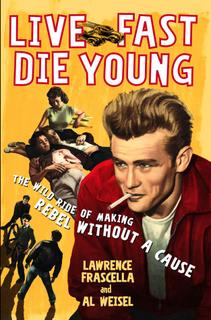

But reducing "Rebel Without a Cause" to symbols only undermines its enduring vitality. It is really a movie of gestures, as Lawrence Frascella and Al Weisel grasp in their lively and intelligent "Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making 'Rebel Without a Cause.'"

When James Dean's Jim Stark returns home, exhausted and troubled, from a game of chicken that has killed one of his classmates, the first thing he does is go to the refrigerator for a drink of milk. He holds the bottle to his forehead, then to his cheek, a movement so smooth and simple you almost miss how elemental it is. Frascella and Weisel trace this small moment to an improvisatory session between Ray and Dean, in which Ray challenged the young actor to find a way to cut to the scene's essence. "It was a startling yet entirely natural move," Frascella and Weisel write. "It possessed an electric charge that carried directly into the film, where it would read as completely true to the sensibility of the milk-fed American teen, caught between maturity and childhood."

So many making-of books seem like deadly procedurals, with the authors stuffing in tons of minutiae just to show how much research they've done; whatever affection they feel for their subject gets buried under all the paperwork. But "Live Fast, Die Young" reads as if Frascella and Weisel took a good look at the movie in front of them and simply asked how and why. That's the reason we learn the story of the milk bottle, as well as the several theories about the origin of the red jacket Dean wears so memorably in the film. Although one source claims the jacket was bought on the cheap at a Hollywood men's store, the movie's costume designer, Moss Mabry, says he made three of the jackets from a bolt of red nylon, carefully working out the size of the collar and the placement of the pockets. "Even though the jacket looked simple," he explains, "it wasn't."

The apparent simplicity of that jacket sums up the difficulties Ray faced in creating what might have been, in less capable hands, just a throwaway teenage melodrama. Frascella and Weisel suggest that Ray was probably motivated to make "Rebel" at least partly by his strained relationship with Tony, his own son from his first marriage.

At 13, Tony slept with Gloria Grahame, then Ray's wife. But the charismatic, temperamental Ray wasn't above scandalous behavior himself: he began an affair with the young Natalie Wood in 1954, when she was 16 and he was 43. Almost immediately after she took up with Ray, Wood also started sleeping with Dennis Hopper, whom Ray had just cast in "Rebel." When Ray learned of Wood's infidelity, months later, he punished Hopper by giving nearly all his lines to another character. (Even so, Hopper reconciled with Ray many years later, getting him a teaching job when he really needed work.)

But the director's truest love affair, though not a carnal one, may have been with Dean himself. The most fascinating sections of "Live Fast, Die Young" deal with Ray's relationship with his mercurial, seductive, frustrating star, a cosmically gifted performer prone to self-indulgence and erratic behavior. Immediately after meeting Dean (who had just completed "East of Eden" with Ray's mentor, Elia Kazan), Ray knew he wanted him for "Rebel." But the courtship wasn't quick or easy. "We sniffed each other out, like a couple of Siamese cats," Ray said. And even after Dean signed on to the film, the tension between actor and director never dissipated.

Although Dean is rightly considered one of the greatest Method actors, he often abused some of the Method's tenets. Dean was injured by one of his fellow actors, Corey Allen, after insisting that real switchblades be used in the movie's knife-fight scene. When Ray instinctively stopped the camera, Dean was furious: "Can't you see this is a real moment? Don't you ever cut a scene while I'm having a real moment!" Dean would sometimes curl into a fetal position before beginning a scene, or keep the other actors waiting as he holed up in his dressing room, preparing. "What the hell does he think he's doing?" one crew member grumbled. "Even Garbo never got away with that."

Had Dean lived longer, his obsessiveness might have become unbearable to his peers and everyone else. But he left so few perforamances behind - and such great ones - that we can allow him a few indulgences. In "Live Fast, Die Young," Corey Allen explains how Dean helped redefine Hollywood's idea of masculinity: "These days, we talk about vulnerability very easily, partially because of people like Dean who were willing to put it on the line." On the set, Dean may have gotten away with indulgences that wouldn't have been granted to any other actor. Then again, not even Garbo was James Dean.

Rebel Without a Cause, James Dean, Nicholas Ray, Natalie Wood, Sal Mineo, Film, Movies, Books, New York Times

No comments:

Post a Comment