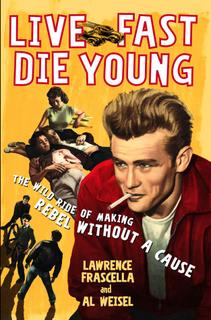

Perhaps the most poignant memory that Lawrence Frascella and I have of researching our book Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause, was the day we met the composer of the score of Rebel Without a Cause, Leonard Rosenman, who died this week at 83. We were looking forward to meeting Rosenman, whose penetrating intellect we already admired from the interviews he had given in the past about the film.

Perhaps the most poignant memory that Lawrence Frascella and I have of researching our book Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause, was the day we met the composer of the score of Rebel Without a Cause, Leonard Rosenman, who died this week at 83. We were looking forward to meeting Rosenman, whose penetrating intellect we already admired from the interviews he had given in the past about the film.We wrote to him asking for an interview and soon received a reply from his wife, Judie, who had some devastating news. Her husband, she said, was suffering from frontotemporal dementia. Although he occasionally had lucid moments, she doubted he would be able to remember very much. But she invited us to come see them and said she would do whatever she could to help. When we arrived at their home in Los Angeles, Rosenman greeted us warmly but it soon became apparent that he would be unable to talk about Rebel Without a Cause or any of the other films he worked on or the people he worked with in any detail. He told us a couple stories he had already told before many times, such as about his first meeting with James Dean, but he couldn't remember anyone's name or the names of the films. He called Dean "that guy" and referred to East of Eden as "film one" and Rebel as "film three." It was heartbreaking to see him struggle to remember those days.

But then something extraordinary happened. He sat down at the grand piano in their living room and asked us if we wanted to hear some of the music he composed for Eden and Rebel. He then played some of the themes from those films beautifully, note for note. The disease had mercifully left this part of his mind untouched. We were moved to tears. When we told Gail Levin, the director of the PBS American Masters biography of Dean, about this, she filmed Rosenman playing one of the themes to Rebel, which you can see here (the link to the footage is in the upper-righthand corner) or embedded below.

Judie then said she would take us to meet Rosenman's first wife, Adele, who was married to him when he composed these scores and we spent a wonderful evening with her as she reminisced about that time. She told us how Rosenman composed the score to Rebel in an apartment building (where Dean also lived) that was across the street from Warner Brothers during a hot summer. The apartment had no air conditioning so they had the windows open and one day Jack Warner telephoned to say, "Stop playing that music or close the windows!"

The Rosenmans met James Dean at party after a New York performance of Woman of Trachis for which Rosenman had composed the music. The host of the party started playing a Mozart piano piece badly and before she could assault their ears with the second movement, Rosenman said that Adele could play it beautifully. She said she didn't have her glasses so Dean lent her his. A month later Dean showed up at their apartment late one night clad in black leather, looking "like a member of the Gestapo," Rosenman once said, and asked the composer for piano lessons. Although Dean was not a very good piano student, they became good friends and Dean recommended Rosenman to Elia Kazan to compose the score to East of Eden. Rosenman thought of himself as a serious avant-garde musician and didn't want to do it at first. At the time the only "serious" composer who had written a film score was Rosenman's friend Leonard Bernstein, who wrote the score to On the Waterfront. Unfortunately, once Rosenman started composing scores in Hollywood it would be 20 years before another of his pieces would be performed in a New York concert hall again. At the time serious composers did not write for the movies.

Rosenman composed the music for Eden before the film started shooting and he sometimes played the music on the piano on the set as the scenes were shot, which is the way that some Russian film composers worked. Rosenman's next score, for The Cobweb, was even more innovative. It was the first 12-tone score ever composed for a film. Rosenman had once studied with Arnold Schoenberg and his atonal technique was perfectly suited to a film set in a mental hospital.

Rebel's director Nicholas Ray met Rosenman and Dean on the same day when Kazan invited Ray to see a rough cut of Eden. Rosenman played the piano while Dean sat in the back looking bored. Rosenman was not only hired to compose the score for Rebel, he took part in much of the improvisatory preparation of the film and was present at the first script reading. In fact, Rosenman helped Ray find Stewart Stern to write the script after Ray had already fired two screenwriters. Rebel might never have gotten made if it weren't for Rosenman.

Rosenman once described the music for Rebel as having "a lot of jazz in it but it was like a twelve-tone type of jazz." The music Bernstein composed for West Side Story is clearly influenced by Rosenman's score for Rebel which premiered two years later (although Stephen Sondheim denied it when I asked him about it). The score is as innovative for the music he left out as it is for the music he composed. At the time most film music played continually throughout a film, but Rosenman thought that long passages of silence can sometimes be just as effective. That was not always true, however, as Rosenman learned. Rosenman had not composed any music for the police station scene in Rebel, but when some preview audiences laughed at the scene where Dean hits the desk, Warner's music director Ray Heindorf asked Rosenman to compose a short piece of music to play afterwards, which effectively stopped the audience from laughing to Rosenman's surprise.

Rosenman revolutionized film music. At a time when most film scores were heavily influenced by 19th-century Romantic European composers, he took film scores into the 20th-century, stirring serialism, the rhythms of Béla Bartók and Igor Stravinsky, the romanticism of Aaron Copland and jazz into a potent mix. Although Rosenman won two Oscars, ironically they were for arranging the music in Barry Lyndon and Bound for Glory and not for composing. Other notable scores he composed include Beneath the Planet of the Apes, Fantastic Voyage, the 1978 version of The Lord of the Rings, Cross Creek, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, September 30, 1955, Making Love, A Man Called Horse, television's Sybil and Friendly Fire, for which he won Emmys, and music for the TV shows The Defenders, Combat! and Marcus Welby, M.D. I hope that as more people hear his work he will finally get his due as one the most important and influential film composers in history. But as for me, I will always remember the day when this warm and gentle man sat at a piano and moved us all so deeply with the power of his music.

Leonard Rosenman playing the theme to Rebel Without a Cause, 2005

The opening credits of Rebel Without a Cause.

Scenes from East of Eden set to Rosenman's score.

Technorati Tags: Rebel Without a Cause, Leonard Rosenman, James Dean, Nicholas Ray, Elia Kazan, East of Eden, Film, Movies, Books

4 comments:

I was a teenager when I saw the movie. Although the movie was very good, I still feel that that Leonard Rosenman's music was exceptional. It took me many years to find a reocording of the music. And lo and behold, it turns up on Amazon on the internet. I also love Mr. Rosenman's music to East of Eden.

So here's to great music that make great films. I found it very interesting that the music scored after the hand pounding had to power to stop an audience from laughing Ah, the power of music!

Were Aaron Copland, Sergei Prokofiev, Bernard Herrmann--to name a few--not composers of "serious" concert music who did film scores before Rosenman?

Also, just a grammar/syntax thing: S. Sondheim wouldn't "deny" the influence of LR's "Rebel" score on Bernstein ("West Side Story")--only Bernstein could "deny" that--perhaps better to say that Sondheim "dismissed" or "discounted" this assertion.

Then again, go listen to LB's "On the Waterfront" score--a bit before "Rebel," and you'll hear the basis of Bernstein's dramatic/jazzy/urban orchestral sound, WSS being "more of the same."

I saw the film as a teenager in my home town. I mentioned it to my friends who hadn't the slightest interest in the music. I thought it was awesome back then. Only recently did I discover the music on youtube: (1) the love theme only a minute or so long but bittersweet lovely and (2) Scott Dunn conducting a three minute suite of the music. Indeed, the music was ahead of its time.

Thank you for writiing this

Post a Comment