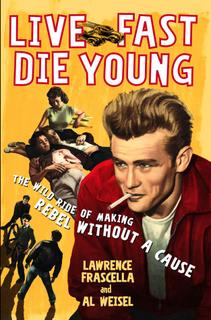

_5.jpg) Actress Betsy Blair, who died in London today at 85, was the first person we interviewed for our book Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause, and it is a story she told us that leads it off:

Actress Betsy Blair, who died in London today at 85, was the first person we interviewed for our book Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause, and it is a story she told us that leads it off:"In the early 1950s, director Nicholas Ray was a regular at the classic Saturday night parties thrown by actress Betsy Blair and her husband Gene Kelly—the kind of exclusive Hollywood soirees that would find Judy Garland singing at the piano, Leonard Bernstein playing charades or Greta Garbo sitting casually on the edge of the Kelly’s kitchen sink. Blair remembers the tall, handsome, seductive Ray with great fondness. “He was always lively and iconoclastic and full of serious opinions,” says Blair, who calls him “a Melville hero” for the way he chased dream projects and battled against the confines of the studio system. Blair knew Ray to be a compulsive womanizer, gambler and drinker, although “never a sloppy drunk.” But one night in July 1951 after their weekly party broke up, Blair and Kelly looked out of their front window and encountered a bizarre sight.

“There was a little slope in front of our house,” says Blair, “and I remember Nick leaving and instead of getting into his car, he sank onto the grass, just sort of lying there. I was ready to go out and get him. But Gene said, ‘Let’s see if he gets up again.’ And so we waited, fifteen to twenty minutes. I think Nick was actually planning to lie there all night. Eventually, we did go out and get him.” Like everyone in Hollywood, the Kellys knew that Ray had just filed for divorce from his second wife, the quintessential film noir blonde, Gloria Grahame, after a stormy three-year marriage, but they had no idea what precipitated the separation. “We didn’t know in the beginning what had happened,” says Blair, “just that they were fighting and breaking up and that he was desperate. And then, when I found out, it was hard to believe.” The real story behind the break-up was shocking even by Hollywood standards."

It was just a coincidence that we started with Blair and that her anecdote introduced our book, but what a wonderful way to start. Blair was in New York promoting her beautifully written and fascinating autobiography, The Memory of All That: Love and Politics in New York, Hollywood, and Paris

I think Blair had a big influence on the way we wrote the book. Talent inspired awe in her but at the same time didn't blind her to people's foibles. She was frank and honest but also empathetic and non-judgmental. And it was in that spirit that we approached the very talented and flawed people we were writing about.

I got a chance to interview Blair again for a piece I did for Premiere on Katharine Hepburn when she died. Blair had worked with her on a film adaptation of Edward Albee's play A Delicate Balance, directed by Tony Richardson. But she had gotten to know Hepburn years earlier when she was invited to luncheons at the house Hepburn shared with Spencer Tracy on George Cukor's estate. The other guests were Greta Garbo and Ethel Barrymore.

"I think I was so thrilled to be invited that I tried to observe everything the three of them did and George teased me a bit about it," she told me. "They were all lovely to me but I was too impressed, too thrilled to be there. I was mostly being a good girl, behaved, eager to jump up and get Ethel Barrymoore's parasol, so my interaction with them was more like the grown-up daughter not quite ready. Garbo was not 'I want to be alone' in that surrounding so I can remember a lot of laughter and quite sharp, not bitchiness but sharp women's, actresses Hollywood talk about studios or directors they didn't like. There was nothing profound or enlightening or artistically thrilling. It was more fun that was being had at George Cukor's lunch. Everybody had fun at George Cukor's anyway. I remember when I first saw them that first day. Both Hepburn and Garbo in beige and white trousers and shirts, sandals, the beautiful hair on Hepburn, big hat on Garbo for the shade, and Ethel Barrymoore being elegant and dignified."

I asked her about Hepburn's relationship with Spencer Tracy and Blair told me, "At the time when I was young and foolish I remember thinking what is she wasting her life for on this man who won't get a divorce? How can she be doing this to herself? But you can't really judge people from the outside." Do you feel differently now? I asked. "I think if that's what she wanted to do with her life it was brave of her to do it. So I guess I do feel differently. I wish she had a different kind of life but maybe she didn't want one, she wanted him. So good," she said.

Working with Hepburn on A Delicate Balance, Blair was awed by Hepburn's preparation: "I once said to [director] Karel [Reisz, her second husband] during the shooting, 'You know she gets up at four in the morning and does all these things before she gets on the set. A hot bath when she first woke up and then exercises then a shower and washing her hair and putting her hair in rollers. She would get into bed with the script for the day and go over it again and then she had this enormous breakfast of bacon and eggs and cereal and orange juice and toast, I mean enormous, a really enormous breakfast and then she would do her makeup before she came to the studio and then get dressed and be picked up by the car. At lunchtime she would have it was called Tiger's Milk it was some sort of vitamin powder you'd put into milk. She'd have a glass of that and sleep for the rest of the hour at lunchtime. And she was perfect for the rest of the afternoon. I said to Karel when I saw all that I thought well I never could have been a movie star really, and he said I don't think you would have had this husband either. She once said to me as she walked past me on the set, 'Oh I never could sit down in my costume.' And of course I felt immediately like a bad little girl."

Blair was blacklisted in the 1950s because of her political views, though being married to Gene Kelly gave her some protection. After their divorce she moved permanently to Europe and married Reisz in 1963. In addition to her Oscar-nominated role in Marty, Blair starred in A Double Life (1947), Another Part of the Forest (1948), and The Snake Pit (1948) and in 1957 she worked with Michelangelo Antonioni in Il Grido. In her book she recounts how she and Antonioni went over the script for two hours when they met. "I can see now that my very American combination of naïve confidence in my opinion and the Stanislavsky approach to acting were completely alien to him," she wrote. "His art is so personal and mysterious. I'm very glad—and lucky—that he didn't decide to drop me then and there." Years later Antonioni said in an interview that the worst professional experience of his life was "The first two hours I spent with Betsy Blair." In tears she showed the interview to Reisz, who told her, "Don't be silly—think of it as a great honor."

I think of it as a great honor that I got to meet her. She was not the most well-known or prolific actress. But from my brief encounters with her and from reading her book I found her to be one of the most remarkable people I have ever met. I wish I had had the privilege to know her better. At the end of our interview with her for our book, she said something I'll always remember. "You get older and you realize that you don’t ever know anything," she said. "You really don’t. You see things and you think you know but you don’t know the truth, only what you saw. It’s all Rashomon."

A Delicate Balance

Marty